|

SECTION 0: General Introduction The previous tutorial examined how “narrow-phase” collision detection works in N; given two shapes (a dynamic AABB or circle, and a static tile), we learned how to project the dynamic object out of the tile. This tutorial deals with “broad-phase” collision detection: given a dynamic object in a world full of tiles, how do we know which objects and tiles it should be tested with during the narrow phase? The solution used in N was to split the world into a uniform grid of square “cells”; instead of testing the dynamic object against all the tiles in the world, we only need to test against the tiles contained in the cells which are touching the dynamic object. The one problem with our approach is that all dynamic objects must be smaller than a grid cell; while this limitation can be circumvented (for instance, by representing a single large object as multiple smaller objects), in actionscript, it really helps keep things running fast. Thus, it was a self-imposed design constraint. Grids tend to work best when all game objects are of roughly the same size and the game world is relatively small; an NxN grid requires N^2 cells, so for larger worlds the memory requirements might be prohibitive. More complex structures which are used to partition game worlds, such as quadtrees or multi-resolution grids, save memory and/or make it easier to support objects of vastly different size. |

|

SECTION 1: Basic Tile Grid The first use of the grid was to store the tilemap data which defines the “solid” parts of the

world; since tile-based games use a grid of tiles, a grid seemed like a good fit ;) The first thing we’d like to be able to do is to determine, given a position, which cell contains this position. This is easily done:

grid_column = Math.floor(pos.x / cell_width);

grid_row = Math.floor(pos.y / cell_height);

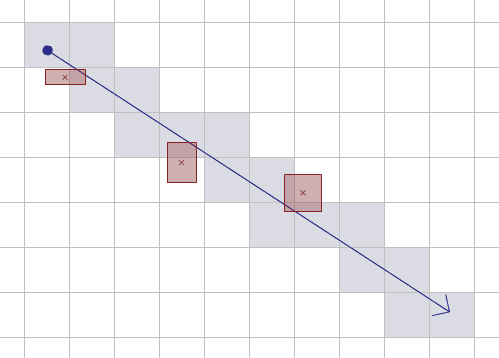

Now we can easily determine which cell contains our dynamic object’s center; we call this cell the current cell of the object. Since we’ve restricted the object’s size to less than the size of a cell, we know that the object can only overlap at most 4 cells. instructions: drag the blue box to move it within its current cell. comments: the grid cells touched by the box are highlighted in red. note that if the object overlaps the current cell’s right neighbor, it can’t possibly overlap the left neighbor; likewise for the up/down neighbors. Figure 0. The Cells Touched by an Object We can safely assume that the object will, at most, be overlapping the current cell, a horizontal neighbor of the current cell, a vertical neighbor of the current cell, and a diagonal neighbor of the current cell; the diagonal neighbor is also a neighbor of the horiz/vert. neighbors. Determining which cells an object overlaps can be done is various ways:

. you can simply use 4 position-lookups (one for each of the object’s corners). We can run into problems if part of the object is outside of the boundary of the grid; this results in the above methods generating cell indices which don’t exist. This can be avoided by using min/max to keep the indices within the limits of the grid, or by using modulo to “wrap” the indices to the other side of the grid. A much simpler solution is to pad the outside edges of the grid with “border” cells, which can’t be occupied by an object; this prevents objects from leaving the boundary of the grid. –= collision vs. a tilemap using the grid =– Now that we know the 4 cells touched by our dynamic object, we need to collide the object against the tiles contained in those cells. The actual collision process is described in the first tutorial. Each cell in the grid stores tile information describing the tile contained in that cell. this includes a flag indicating the shape of the tile, as well as any tile-specific properties needed by the collision routines (i.e. x-width, center position, surface normal). To implement this, you can define a set of tile objects; each tile is responsible for generating collision results between itself and a dynamic object:

tile.Collide_Circle(myCircle)

Or, you can use a simpler c-like approach where both the tile and the object are simply containers of data, and collision functions are stored in a 2D hash-list of collision functions; the shape-flags of the objects being collided are used as hash keys to select the appropriate function:

Collide[tile.shape][myObj.shape](tile, myObj)

|

|

SECTION 2: Advanced Tile Grid –= grid improvements =– Now that we have a simple grid in place for use with object-vs.-tilemap collision, there are certain things we could do to make it more efficient. The first thing is to store, in each cell, direct references to that cell’s 4 neighbors. This way, once we’ve determined an object’s current cell, we can access the neighboring cells using a single property lookup; this results in a smaller number of calculations when accessing neighboring cells but causes each cell to occupy more memory. Since the cost of calculating cell indices is likely to be negligible in many programming environments, this trade-off might not always be worthwhile. In N we implemented these neighbor “pointers” separately:

cell.nR //right, left, up, down neighbors

cell.nL

cell.nU

cell.nD

–= edge info =– One major enhancement we made to our grid is to store information, not only about each cell, but about each of the cell’s 4 edges. This idea was borrowed from an article in Game Programming Gems 3 [Forsyth] which mentioned that the game X-Com used a similar structure. The edge data we stored was very minimal; a single flag which indicates the state of the edge:

. empty: neither of the cells which share this edge contains a solid tile shape Once each tile has been assigned a set of edge states, we then need to compare the edge states of neighboring tiles; any edge at which both tiles have solid edge states should be considered empty, as such a configuration only exists below the surface of the world. Such a change will have no impact on the correctness of the collision results, since objects should only collide with the world’s surface. Having this edge info let us skip a lot of tile-specific collision routines; if an object overlaps a solid edge (which is very common in tile-based games), we simply project it out of that edge instead of having to resort to a more complex object-vs.-tile collision test. Since the only edges which were labeled “solid” are those which perfectly match the shape of a tile, the result is the same as if we had used an object-vs.-tile test, but it’s much simpler to compute. The only time we have to resort to tile-specific collision routines is when an object touches an “interesting” edge. This edge information can be considered a coarse approximation of the surface of the world described by the tilemap; this is sometimes useful since a normal tilemap doesn’t contain any explicit surface information, and knowing the surface of the world is often useful — for instance to allow enemies to move along the world’s surface. Having this extra edge info for each cell may or may not be useful in your game. In N, doors were easily implemented as objects which changed the value of a cell’s edge states. This was a pleasant side-effect of using edges. Additionally, the enemy AI uses edge states for pathfinding; this lets enemies respond to doors, and follow the (approximate) surface of the world. Our ray-queries were also sped up by using this edge info. Unfortunately, the state of each edge is determined by the state of the two cells adjacent to it; the logic we implemented to correctly setup the edges was complex and quite prone to bugs, since we had to consider each possible combination of cell states. A simpler method to setup/define edge states probably exists; please let us know if you come up with anything. |

|

SECTION 3: Object Grid The grid structure described above can also double as a spatial database used to manage dynamic objects. Just as each cell contains information about the tile located in that cell, it can also contain information about each dynamic object currently located in the cell. Each cell contains a list of dynamic objects; as an object moves through the grid, we insert/remove it from each cell’s list as appropriate. There are two approaches that can be taken when using a grid with dynamic objects: “normal” grid: each object is associated with all of the cells it touches. In our case, this would be from 1 to 4 cells. Every time the object moves, it’s removed from the cells which it used to touch, and inserted into the cells which it now touches. When we collide an object, we only need to test it against the contents of any cell it touches.

. pros: each object needs to look in at most 4 cells to find other objects it might collide

with “loose” grid: each object is placed in a single cell: that which contains its centre. When an object moves, it’s removed from that (single) cell and inserted into the cell which contains its new position. When testing for collision, we have to check not only the current cell, but the 8 cells neighboring the current cell. The idea of a “loose” grid can be a bit confusing until it clicks, at which point everything will make perfect sense. You can find more details here: [Ulrich]

. pros: each object needs to be inserted/removed from only 1 cell when it moves. We chose to use a loose grid in N because it simplified handling moving objects; however, most of the ideas mentioned in this tutorial apply to any kind of grid. Each cell in our grid stores a double-linked-list of references to objects; the objects in a cell’s list are those whose centers are contained in the cell. (If you’re not familiar with linked-lists, googling “linked list” is probably a good way to learn about them.) In our implementation, each cell has:

.next //the head of the linked list and each object has:

.cell //reference to the cell in which it’s contained Whenever an object moves, its position in the grid is updated and changes to the linked lists are made as appropriate. –= more details =– There are two ways to approach broad-phase collision. One is to let each object query the world to find other objects it might be colliding with. Another is for a manager to find all possible collisions, and notify the objects involved. In N, we used the first method because it allowed a very simple design: only the ninja queries for collision, and the other objects are notified if the ninja’s query results in a collision event. While this is good from the point of view of execution speed, it also limits possible designs. For instance, enemies can’t react to each other (as in Super Mario Bros., where goombas which walk into each other change direction). So, each frame the ninja tests its current cell and the 8 neighboring cells for objects; it tests for collision against any objects found. A more general, elegant system, which is useful in simulation-type environments where all objects must collide with each other, is to iterate over all moving objects, and test them against: . any objects after them in the current cell’s list It might seem like this technique will miss some collisions, but if you work it out on paper you’ll see that every possible collision between objects is found. This lets us reduce the number of per-object cell-list tests to 5 (from 9), without resorting to flags or any other awkward solution. Collision detection in any game is very specific to the game’s design; usually you can achieve significant increases in efficiency by simply choosing good rules for your game world. For instance, in a game such as Soldat where there are many moving objects, most of which are bullets, a very good idea is to decide that bullets should not collide against other bullets. This means that bullets don’t have to be moved in the grid every time they change positions — instead of being in the grid, they simply read from the grid to determine which objects they might collide with. This saves the cost of numerous linked-list insertion/removals; the tradeoff is that you can’t stop your opponent’s bullets with your own. |

|

SECTION 4: Raycasting Aside from projection/collision queries, games often also need other types of queries; objects can invoke these queries when they need to know something about the world. A good example of such a query is a raycast; a ray is simply a line with only one endpoint. Rays can be used to determine if two objects can “see” each other, or can model a fast-moving projectile — for instance, in Quake, many weapons (such as the railgun) are modeled as rays. We might want to know the first thing that the ray intersects (by first we mean the intersection point closest to the ray’s origin); or, given two points we might want to know if the line which connects those two points intersects anything. In N, we use raycasts to determine AI visibility, as well as for some of the weapons. . broad phase: determine which things (tiles and objects) the ray might collide with –= broad phase =– In our grid-based system, the broad phase amounts to determining which cells the ray touches; anything not contained in this set of cells can’t possibly touch the ray. (NOTE: since we use a loose grid for our objects, this isn’t strictly true; see below for more details) A naive approach to determining which cells the ray touches might be to calculate the AABB containing the ray, and consider all cells touching this AABB as touching the ray. While this works well for short rays, or rays which are almost vertical or horizontal, it requires testing up to n^2 cells, which will get very slow very fast. A better solution would be to determine EXACTLY which cells the ray touches; a great (and quite simple) algorithm to do this is described in [Amanatides] and [Bikker]; basically, it lets us step along the ray, visiting each cell the ray touches in the order it is touched by the ray. For N, we simply implemented this algorithm; at each cell we test the ray against the cell contents, using our narrow-phase routines. –= narrow phase: vs. tiles =– Not only does the above ray-traversal algorithm tell us which cells the ray touches, it also allows us to efficiently calculate the points at which the ray enters and exists each cell — i.e. the points at which the ray crosses the edges of the grid. This is very useful because, since our grid stores edge info, we can stop as soon as the ray crosses over a solid edge — we know that this is an intersection without having to perform any special ray-vs.-tile intersection test. If the ray crosses an interesting edge, we need to test the ray against the cell’s tile shape using a tile shape-specific test. Most of the tests we used were implemented as ray-vs.-line or ray-vs.-line-segment tests, based on the following sources: Geometry Algorithms and [O’Rourke]. For the circular shapes, we adapted a swept-circle test [Gomez]. –= narrow phase: vs. objects =– One major problem with using a loose grid is that objects which aren’t contained in the cells touched by a ray might still touch the ray.

In N, this was a problem we could ignore — since the ninja was the only object which rays needed to be tested against, we simply performed a ray-vs.-tiles test to find the point at which the ray hits the tiles, and then we performed a ray-vs.-circle test against the ninja to see if the ray hit the ninja before hitting the tiles. If intersecting rays with dynamic objects is an important feature of your game, you might be better off using a regular / non-loose grid, which doesn’t suffer from this problem. |

|

SECTION 5: Conclusion / Source Code

As we mentioned before, the one main limitation of our grid-based approach is that all objects must fit

inside a grid cell (i.e. can be no larger than a grid cell). This isn’t really a limitation imposed by

the use of a grid; it’s a self-imposed limitation designed to increase the simplicity and speed of

this

approach.

To use a grid-based approach with any size of object, all that’s necessary is to be able to (hopefully quickly) determine which cell(s) an object touches, so that it can be inserted/deleted from those cells’ linked lists. With objects smaller than a cell, this is very fast; as the size of an object grows, the number of cells it touches increases, and the cost of the linkws-list insertions and deletions will become prohibitive. The best grid resolution to use is game-specific. Another thing to note is that you don’t need to have a tile-based world to use a grid; using the previous tutorial’s collision routines and a grid-based system, you could develop an engine which supports a world composed of arbitrarily placed and sized shapes; this way your world wouldn’t have to be constrained to tile-sized blocks. All you need to be able to do is, given a shape, determine all of the tiles it overlaps. If you insert each static object into the grid this way, you can then use the grid as you would with tiles — to find all the static objects to test a dynamic object against. Anyway, hopefully you’ve learnt that a simple grid can often be an effective data structure to use as a spatial database in your game, and also how to go about using it. –= source code =– Here is a demo application containing the N source code relating to this tutorial: You are free to use this code however you’d like, provided you notify us if it’s for commercial use; a link to our site would also be appreciated. –= contacting us =– Please let us know if you have any corrections, comments, or suggestions about this tutorial. PLEASE don’t contact us with questions about the source, you’ll just have to figure it out on your own. |

|

Amanatides, John. A Fast Voxel Traversal Algorithm for Ray Tracing ( mirror ). Bikker, Jacco. Raytracing Topics & Techniques – Part 4: Spatial Subdivision ( archived ). Forsyth, Tom. Cellular Automata for Physical Modelling ( mirror, full book ). Gomez, Miguel. Simple Intersection Tests for Games ( archived ). O’Rourke, Joseph. Computational Geometry in C ( archived, full book ). Simpson, Zachary. Design Patterns for Computer Games Ulrich, Thatcher. Spatial Partitioning with Loose Octrees ( mirror, archived ). |

| (c) Metanet Software Inc. 2004 |

Tutorial B

Original by Metanet Software, 2004 (current version,

archived

version).